I was sitting at Bahama Breeze with a group of faculty and students after a long day at residency last month. Across the table sat another faculty member, and I tried to describe him to a new colleague next to me. But I couldn’t see his face, or anyone’s, on that side of the table. The lighting was uneven. I was in the darker center section, while he sat in front of a bright window. And with my poor eyesight, that might as well be a wall of light.

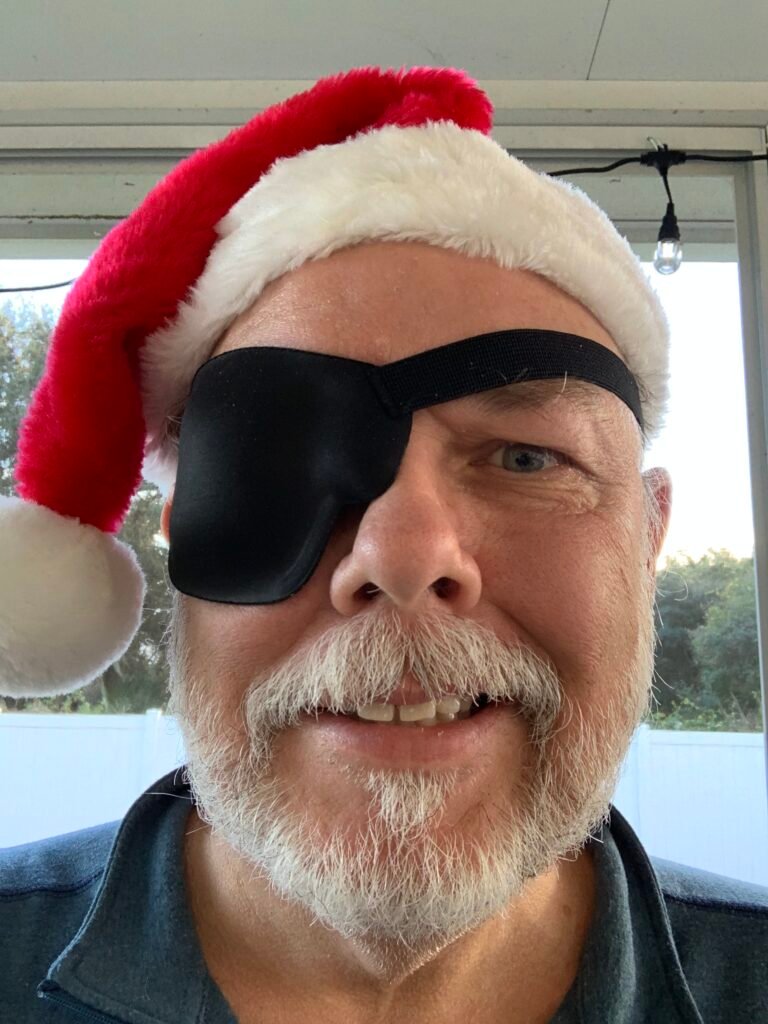

I’m blind in one eye. Both my eyes have been through more procedures than most of my student body go through in a lifetime… corneal surgeries, scleral bucklings, pneumatic retinopexy, radial keratotomy, laser photocoagulation, cryotherapy. My vision is a patchwork held together by science, determination, and a little grace. So, I described him the only way I could: by his voice, the way he leaned into the conversation, the tone he used when he jumped in with a joke.

The colleague beside me was surprised by how little I could see. His reaction reminded me of something we often forget: not everyone sees the world the same way. For some, vision is crisp and reliable. For others, like me, the world arrives in fragments. I have to assemble meaning from tone, energy, rhythm, posture, and years of listening deeply to people.

But here’s the strange thing. Even someone with perfect eyesight can fail to see what matters. Someone across the table might look at me and think, “just another white guy.” Someone who hears my voice or sees my name might think, “just another old white guy.” Their eyesight is technically correct. They see the wrinkles, the age spots, the thinning or non-existent hair. But it’s a shallow vision, a kind of blindness that mistakes a body for a biography.

My physical eyesight may be limited, but I refuse to let my perception be. I’ve spent decades learning to read what can’t be seen: the tremor behind someone’s laughter, the hesitation in their breath before they answer a painful question, the way their shoulders lift when they feel safe. That is vision too. Maybe the more important kind.

And now, I’m preparing for cataract surgery this week on my only seeing eye. For most people, this is routine, an outpatient procedure with predictable outcomes. For me, it’s something else entirely. This eye has been cut, frozen, lasered, stitched, and saved multiple times. Scar tissue, fragile structures, and a long surgical history turn a common operation into a real risk. If something goes wrong, I could lose the rest of the vision I have.

That possibility sits quietly in the background of my mind. It sharpens the urgency of ordinary moments, the way Pierre looks at me across the room when I say “walk”, the color of the sky at dusk last night, the outline of Dawn’s face as she laughs at something I don’t quite catch. It also sharpens the point I keep circling back to, that sight is not the same as vision.

Sight can dim. Vision can deepen. Eyes can cloud. Insight can grow clear. And maybe that is the real invitation here. To move through the world in a way that isn’t dictated by labels or appearances. To stop reducing people to the first thing we notice. To see others with more than one sense. To honor the complexity, the history, and the soul that sits right in front of us.

Because what we take in with our eyes is only a fraction of who someone is. The rest, character, wisdom, warmth, integrity, courage, contradiction, and longing, require something beyond eyesight. It requires real vision.

Dr. Wesley