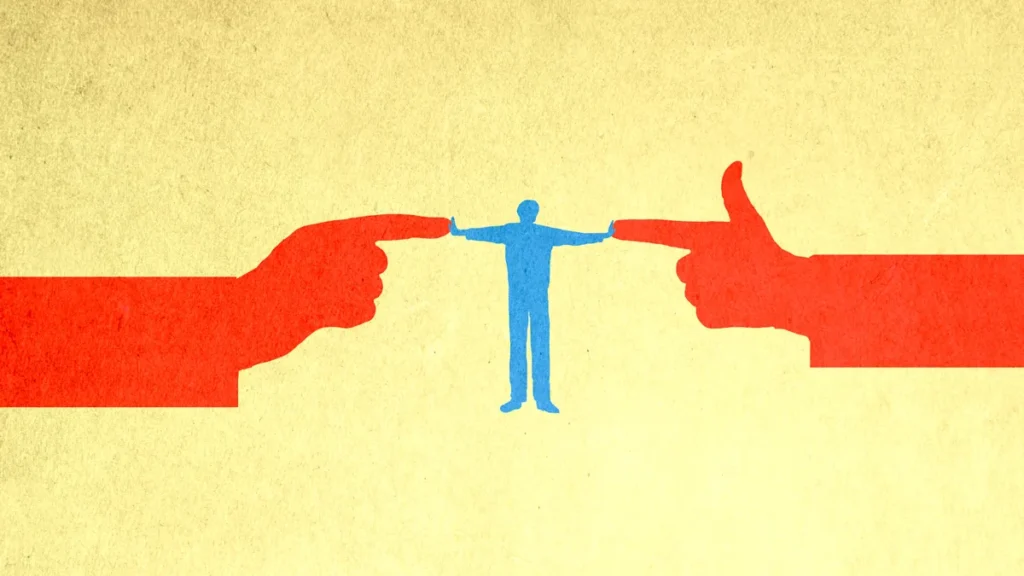

We’ve reached a point where words carry more peril than meaning. Entire friendships, careers, and communities can fracture over a phrase that was meant to build connection, not tear it down. What should be normal human dialogue has become a minefield, and everyone seems convinced the other side is the only one creating the danger.

The left has long shaped cultural rules about language, changing labels, softening terms, and policing vocabulary as if the words themselves cause the harm. The right, meanwhile, once mocked that sensitivity. But now they’ve adopted the same instincts. They’ve built their own list of forbidden words and symbols, their own purity codes, their own form of linguistic fragility.

And we’re all caught in the middle, trying to remember what we’re allowed to say this year.

You see it in the rejection of perfectly accurate terms that somehow become taboo. You see it in the churn of new labels emerging without consensus from the very communities they’re supposed to represent. You see it in the push to replace blind with visually impaired, or deaf with hearing impaired, even though the Deaf community proudly uses Deaf and rejects softer language. The sensitivity isn’t consistent; it’s selective.

And then there was Latino/Latina, which has worked linguistically fine for centuries. Someone decided it wasn’t inclusive enough, and suddenly Latinx appeared… a word almost no Latino people use and many openly dislike. It’s a perfect example of a cultural shift driven more by ideology than by the people it supposedly honors.

The list keeps growing. Words like disabled replaced with differently abled. Pregnant woman erased in certain circles in favor of pregnant person. None of these shifts came from mass consensus. They came from a tiny group declaring new rules that the rest of us are expected to memorize.

You see it in the pronoun rituals, where email signatures turn into public identity declarations. We don’t list our religion there. We don’t include our medical diagnoses. We don’t say “divorced twice,” “recovering perfectionist,” or “still figuring life out.” Yet somehow, pronouns have become a moral litmus test… a way to show whether we’ve pledged allegiance to the right tribe.

And you see it in the mirror-image sensitivity on the right, where words like equity, inclusion, diversity, systemic, intersectionality, or lived experience provoke the same emotional response that MAGA, patriot, or heritage provoke on the left. Each camp claims to be protecting truth and decency. Each one insists the other is hypersensitive, fragile, and irrational. Meanwhile, both are reacting with equal force.

Symbols get the same treatment. A MAGA hat or a Confederate flag sends one crowd into outrage. A Black Lives Matter flag or an Antifa symbol does the same in the opposite direction. Both sides are convinced their reactions are rooted in truth, and the other side’s reactions are rooted in fragility.

One side preaches intersectionality to elevate those they see as historically oppressed. The other side pushes for colorblindness and individual merit. Each side claims the ethical high ground. Each side demands that others honor their sensitivities while dismissing the sensitivities of the people across the aisle.

Somewhere behind all this vocabulary and symbol warfare, real people are trying to talk. Or at least they used to.

I learned this the hard way.

Years ago, I had a colleague I considered a close friend. We laughed together, worked together, shared stories about our families, and trusted each other with the kind of things you only tell people who matter. We also came from different racial backgrounds; she was Black, and I, as I jokingly said at the time, was somewhere between tan and transparent, depending on the season.

During one of our conversations, we drifted into discussing race. Wanting to affirm our closeness, I said something I had always meant as a compliment. I said, “I don’t see skin color in our friendship.”

I meant it in the most human way possible, not that I was blind to the obvious, but that her skin tone wasn’t a condition for my care, trust, or loyalty. I was making a bid for connection.

It landed like an insult.

Her response was immediate, sharp, and deeply emotional: “Well, you better see me as Black. You’d better see me as a strong Black woman.”

The force in her voice stunned me. She didn’t ask what I meant. She didn’t try to understand the intention behind the words. She reacted to the phrase, not the heart that offered it. And in that reaction, the friendship fractured. We never returned to the ease and warmth we had before.

I lost a friend because a sentence carried a meaning she assumed, not the meaning I intended.

I’ve formed many friendships since then with people whose skin color is different from mine, and some of those relationships have been life-giving. But her reaction left a mark. It planted a hesitation in me, not about people, but about conversations like that one. A reflexive caution. A second-guessing of whether an attempt to connect might be misread as an attempt to diminish. And that, honestly, is a loss for all of us.

Years later, I think about my late, missed friend, Joffrey Suprina. Joffrey was openly gay. I was raised in a conservative evangelical world. He came from a worldview that saw the world through a very different lens. We traveled together, shared hotel rooms at conferences, and had long, unfiltered conversations about our lives.

We were honest with each other. Curious. Respectful. And never once did I fear offending him or him offending me. We weren’t policing language. We weren’t checking each other’s vocabulary for ideological purity. We were two men trying to understand each other’s worlds.

And because of that, nothing was off-limits. Nothing was taboo. Nothing was a threat.

You could call it a friendship built on radical goodwill; the idea that we’d interpret each other’s words through the lens of trust, not suspicion.

We desperately need that again.

We need people who can talk across the aisle, across identity, across belief systems, without instantly assuming the worst. We need people who can explain how words land in their community without shaming someone for asking. We need people who can say, “Here’s how I hear that,” without turning every conversation into a courtroom.

We need people who are looking for connection, not correction.

Because until we get back to that, our country will keep tearing itself apart with arguments about vocabulary, while the real work of understanding each other never happens.

Dr. Wesley